破碎的花瓶

致 阿爾伯特·迪克拉爾

這株馬鞭草逝去的花瓶

伴隨著扇子一擊而破碎;

這幾乎輕輕的一觸:

它的聲響微不可聞。

可這裂痕,輕柔又細密,

一天天咬噬著她水晶般的軀體,

邁著隱隱不見卻又堅定的步伐

緩緩地巡遊於她的嬌軀。

她清澈的水一滴滴地泄露出來,

鮮花的汁液漸漸地乾涸委頓;

人們仍未猶疑;

不要碰她,她開裂了。

常常我們摯愛的柔荑,

也使心靈枯萎,使之死去;

然心靈仍自破碎分離,

她的愛之花已然凋謝;

眾人的目光視之如常,

裂紋猶自生長並低低啜泣

她的傷口既深又細;

她開裂了,不要碰她。

一樣的花瓶,不一樣的普呂多姆和納蘭性德···

本文最初發表於我和妻子的微信公眾號: 人面魚Fisage, 有增改。

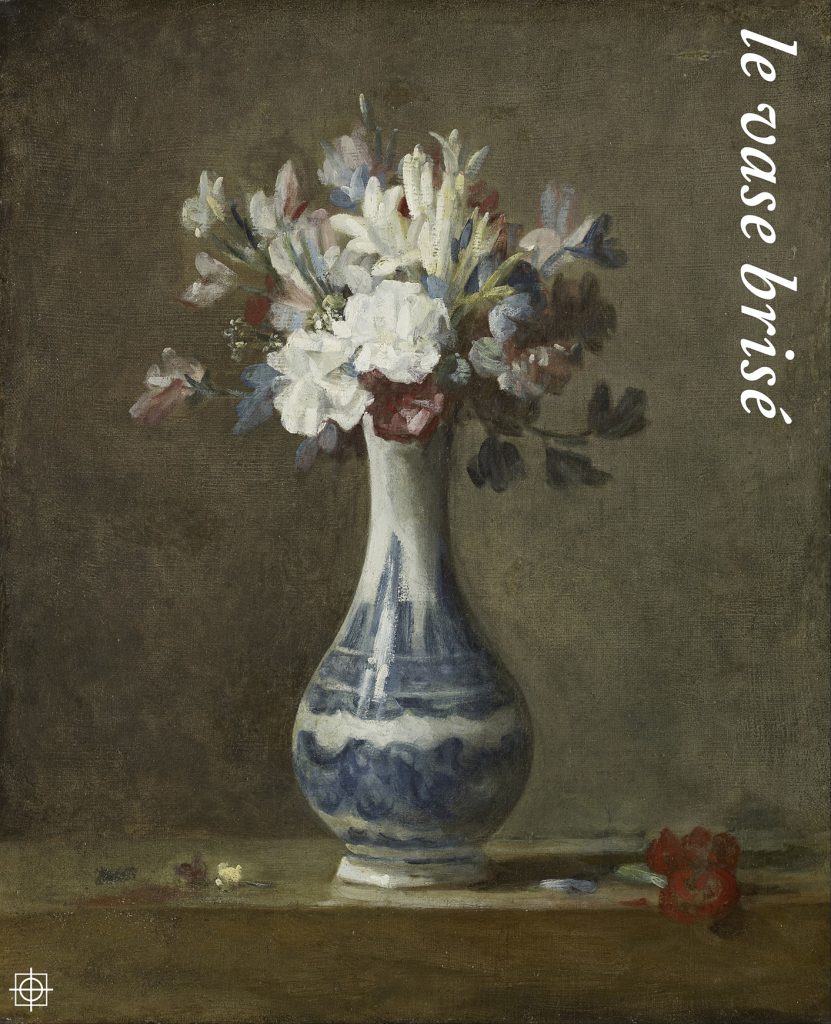

蘇利·普呂多姆(Sully Prudhomme, [1]) 這首《破碎的花瓶(Le vase brisé)》, 寫的既是水晶花瓶,也是在戀愛中受傷、破碎的心靈。在西方文化裏,花瓶既是是容器的象徵,也是女性形象的象徵,無論是基督教和東正教神學裏聖母瑪利亞作為誕生基督的容器而言,還是無數西方經典繪畫裏女性凹凸有致,曲線優雅的背影,都是花瓶完美的譬喻和再現,更何況在十七世紀的尼德蘭(Netherlands, Nederduits, [2])靜物畫還是法蘭西古典繪畫大師的筆下,花瓶近乎就是不可或缺的存在。

詩歌的意象從插有馬鞭草的花瓶開始,一步一步,帶著舒緩而輕柔的節奏,把破碎的花瓶、枯萎的鮮花、愛人的手和破碎的心靈糅合在一起,像是電影中緩緩流逝的時間,鏡頭淡入淡出,描繪了一系列這樣的畫面: 在幽暗靜室中花瓶,貿然遭受隱隱一擊,出現斑紋,開始緩緩裂開,裂紋佈滿全身,水滴一點一點隨著游移的裂紋滲透出來,瓶中花朵在流逝中漸次乾涸、枯萎,最後,花瓶崩裂為一桌碎片,花枝和花瓣的殘骸埋在晶瑩的碎片間猶自嘆息······

普呂多姆在這一連串的憂傷、華美的意象中置入了戀人的手,我們說摯愛的人兒,有時候,看似不經意的輕輕一擊,沒有意識的言語冒犯,還是並非刻意的一個行為,都可能對愛人造成不可挽回的傷害: 因為,戀愛中的人們,心靈都是如此地敏感脆弱而易受傷害,所有的快樂和痛苦,一切的一切,都會在愛情中被無限放大,無限強化,僅僅不過是無心之失,有時都會造成長久的傷痛。在這裡,花瓶不僅僅是愛情的象徵,也是心靈的象徵。普呂多姆細緻入微地刻畫了一顆在強烈慟人的愛情中敏感多情,渴望被愛又容易受到傷害的心靈,並使之和一個破碎的花瓶的意象完美地結合在一起,這不禁令我想起,古典中文世界中的另一個大詞人,納蘭性德 [3] 的《夢江南》:

昏鴉盡,小立恨因誰? 急雪乍翻香閣絮,

輕風吹到膽瓶梅,心字已成灰。

這首詞的最後兩句和普呂多姆的《破碎的花瓶》在意象上異曲同工: 都是花瓶,都是受傷或死去的心靈。納蘭性德從一個古典的東方意象開始–黃昏暮色中飛逝的鴉群–主人公獨自立於靜室之內,渺渺茫茫,窗外大雪紛紛,猶如柳絮飄飛滿天,一陣寒風吹來,膽瓶中的梅花漸次枯萎、凋零,心形焚香已燃盡成灰,只餘下淡淡的暗香縈迴不去,就像是我們人生中那些剎然邂逅燦然卻又無果的愛情,雖令人心動不已,但還是有緣無份,看那繁花似錦,終不過落得白茫茫一片真乾淨,唯若有似無的馨香還殘留在我們的記憶深處,在人生點滴斑駁而晦澀的暗夜之幕上,還偶爾回映出她們昔日褪色的淡淡容顏······

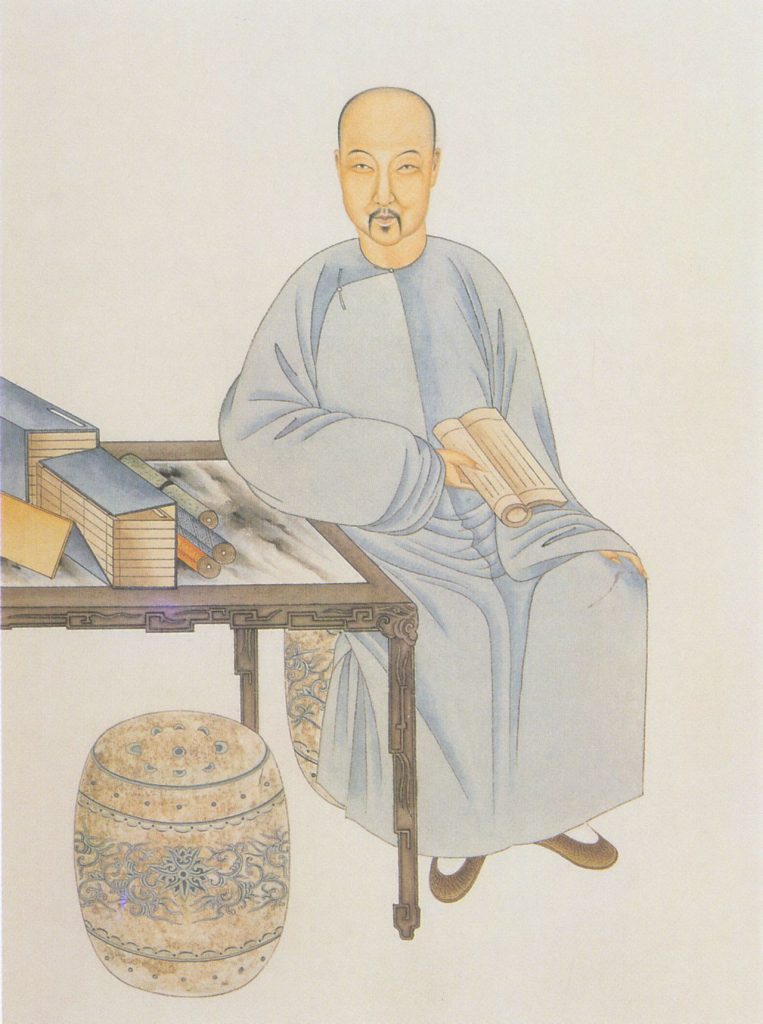

Chen Hongshou, Flowers in a Vase, pigments on silk

也許,我們可以把其歸結於不同的文化傳承和美學理念,相似的意象,東西方兩大詩人處理的手法迥然不同: 普呂多姆從馬鞭草開始,一筆一筆慢慢地刻畫出完整的畫面,力求清晰明了,把意象的細節盡可能地描繪出來,不論是馬鞭草,還是打擊的聲響,花瓶水晶般的質地,緩緩展開的裂紋,漸漸滲透的水滴,以及最後枯萎的鮮花,按照時間推移的順序,一步一步地慢慢展開來,花瓶和心靈意象的融合也是順理成章,自然而然。反觀納蘭性德,他從一個常見的意象(昏鴉)開始,以一種粗略的筆法點綴出一系列不同的意象,它們之間並沒有明確的界限,只有模糊而黏連的過渡,似電影中的蒙太奇(montage, [4]), 一系列並置的意象本身催生了俱有詩意的畫面和想像,而非拘泥於單一鏡頭的敘事和描繪,無論是昏鴉、幽室、雪花、清風、膽瓶還是心字香,這些傳統東方審美意象的詩意連接,本身就是極富有情趣的景象。可以說,普呂多姆用的是西方傳統的寫實油畫手法,從素描研究和草稿開始,一步一步理性地建構起畫面和主體,他充分地考慮了構圖、形體和色彩,在深思熟慮後開始描繪並達成可預見的效果。納蘭性德正好相反,他的處理類似於東亞繪畫中清雅寫意的手法,沒有固定或嚴謹的考慮,隨性而發,詞牌僅僅是提供了一個可供參考的範本,類似於畫譜般的存在,在筆墨白描間略施淡彩,隨手點綴間把不同的意象勾連出來,在意象和畫幅的不同轉換間交織出俱有敘事效果的絢爛鏡頭,並給讀者留下了大量的想像空間,如同中國畫中的留白和音樂裏的休止,讓讀者自己來填充其中豐富而深刻的意藴。–可以說,這是兩種幾乎相反的藝術手法,一個理性、精確而專注,注重於單一畫面的完整和獨立;另一個則感性、隨意而自然,流連於不同畫面間的關係而產生詩意和美感。

可以說,這幾乎是詩歌裏“阿波羅精神(太陽神精神, Apollonian, Apollinisch, [5])”與“戴奧尼索斯精神(酒神精神, Dionysian, Dionysisch, [5])”的兩個美妙案例: 一個清晰、冷靜而外觀,像太陽神無所不在的目光一般洞察纖毫,邏輯精確而分明,力求沒有任何模糊或者不清楚的部位;另一個則模糊、感性而內省,像隨時處於酣醉而半睡半醒的酒神,外部世界和內在世界的界限並不清晰,一連串的事件發生並沒有具體的關聯或直接的邏輯,有大量俱有多種解釋可能性的部分;某種意義上,這也是西方文明精神和東方文明精神的差異所在: 作為東亞語言的成員,漢語、日語和韓語及越南語等語言並不擅長於精確、細緻入微的描述,和西歐語言相比較,漢語等語言沒有明確的性別(陰陽性或中性), 沒有名詞單復數變化,沒有時間(時態)和地點的精確描述或定義,沒有語態和引語的具體差別,可以根據上下文語境俱有多種的解釋可能性–甚至可能是完全相反的解釋。這也是造成這兩首詩歌處理同一相似意象,卻產生完全不同的效果的原因之一,因為,詩歌的基礎材料乃是語言,語言本身的差異性足以構成藝術上完全相反的兩種效果。

也許,在人類建造巴別塔(ܡܓܕܠܐ ܕܒܒܠ, מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל, Tower of Babel, [6])時,上帝不僅僅是為了不讓人類直達天堂,諸神領域也不僅僅只對人類禁足,也許,上帝還在對人類暗示,語言的差異與分別,還可以造成各種不同的美和不同的感悟,由此,我們的世界和人生才如許的豐富多彩······

Turmbau zu Babe

老彼得·勃魯蓋爾《巴別塔》

註釋:

[1]. 蘇利·普呂多姆(Sully Prudhomme, 1839-1907), 法國著名詩人,第一個諾貝爾文學獎獲得者。

[2]. 尼德蘭(Netherlands, Nederduits),歷史名詞,包括現今的荷蘭、比利時的一部分,十七世紀以來出現了無數的繪畫大師。

[3]. 納蘭性德(1655-1685), 清朝著名詞人。

[4]. 蒙太奇(montage), 一種電影剪輯技術,通過將一系列視點不同的多個剪輯(短鏡頭)組合使用來壓縮空間、時間和信息。最早被延伸到電影藝術中,後來逐漸在視覺藝術等衍生領域被廣為運用。

[5]. 酒神與太陽神精神(Apollinisch-dionysisch), 酒神與太陽神或稱戴奧尼索斯與阿波羅是一種哲學的、文學的概念,一種二分法。西方的文學及哲學家如: 普魯塔克、尼采、托馬斯·曼等,都多以此理論為基礎,作出文學或哲學評論。

[6]. 巴別塔(ܡܓܕܠܐ ܕܒܒܠ, מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל, Tower of Babel), 也譯作巴貝爾塔、巴比倫塔,通天塔,本是猶太教《塔納赫·創世紀篇》(《希伯來聖經/舊約全書》)中的故事,是人類產生不同語言之起源。

Nature morte, fleurs dans un vase (vers 1760-1763)

讓·巴蒂斯·西美翁·夏爾丹《靜物,瓶中花》(約 1760-1763)

EN

LE VASE BRISÉ

À ALBERT DECRAIS

Le vase où meurt cette verveine

D’un coup d’éventail fut fêlé;

Le coup dut effleurer à peine:

Aucun bruit ne l’a révélé.

Mais la légère meurtrissure,

Mordant le cristal chaque jour,

D’une marche invisible et sûre

En a fait lentement le tour.

Son eau fraîche a fui goutte à goutte,

Le suc des fleurs s’est épuisé;

Personne encore ne s’en doute;

N’y touchez pas, il est brisé.

Souvent aussi la main qu’on aime,

Effleurant le cœur, le meurtrit;

Puis le cœur se fend de lui-même,

La fleur de son amour périt;

Toujours intact aux yeux du monde,

Il sent croître et pleurer tout bas

Sa blessure fine et profonde;

Il est brisé, n’y touchez pas.

Same flowers in vase, different Prudhomme and Nalan Xinde…

This article was first published on WeChat official account: 人面魚Fisage, co-authored by me and my wife, it has been revised since then.

In Sully Prudhomme’s [1] “Le vase brisé ”, he wrote about the crystal vase as well as a harmed, broken heart in love. In the Western culture, the vase has a long tradition as symbol of container, and as a symbol of female figure. No matter it is the concept that Virgin Saint Mary as a perfect container giving birth to Jesus Christ in theology of Christian Church and Eastern Orthodox Church , or the sexy, cursive female’s back silhouettes in countless Western classic paintings, they are all the best metaphors and representations of the vase. Further more, in the old Netherlandish still life paintings and under the brushes of classical French masters, the vase is an unreplaceable existence on the canvas.

The image of the Pudhomme’s poem starts from a vase with verbena, step by step, with a slow and soft rhythm, the poet has entangled the broken vase, the withered flowers, the hands of lover and the harmed, broken heart together. Just like the time fleeting slowly in the film with the fade in/fade out effect of the scenes, the poem describes these flowing scenes: there was a vase in a gloomy, dark chamber, it suddenly received a invisible blow and some tiny cracks started to appear on its skin, which had been spreading around its entire body ever since then. The water inside began to ooze and leak from these wandering cracks and the flowers in the vase became dry and withered. Then finally, the vase collapsed into a piles of pieces on the table, and the last remains of flower-buds and branches were buried in the splendid fragments with the unnoticeable signs in the air…

Prudhomme has set the hand of lover into the series of spleen yet beautiful images. As we can say, the beloved ones sometimes give out an inadvertent or careless blow, some words without intending offense, or even some random actions, all of them may give some inevitably damages to your beloved ones: it is because people in love tend to have sensitive, fragile and vulnerable hearts. All the happiness or sorrow, all in all, will be enlarged or strengthened endless in love itself. Sometimes a careless mistake may result in a long-lasting pain in a long run. In this poem, vase is not only a symbol of love, but also a symbol of heart. Prudhomme has depicted a sensitive heart in a touching and moving relationship of love, yearning for love yet fearing of hurt and pain, which has been impeccably combined and blended with the images of broken vase. And it reminds me another great poet in Classical Chinese literature, Nalan Xinde’s(納蘭性德, [3]) “Dreaming Jiangnan(夢江南)”:

The crows vanished into the evening,

Why I still stood here, for whom I was so sad?

Like the flying willow leaves,

the snowflakes of the blizzard was turning around the pavilion,

A whisper of wind blowing into the chamber,

around the plum in the vase,

The heart-shaped incense had burnt into the ashes…

(昏鴉盡,小立恨因誰? 急雪乍翻香閣絮,輕風吹到膽瓶梅,心字已成灰。)

納蘭性德

The last two sentences of the poem are similar in the images to that of Prudhomme’s “Le vase brisé”: both are vases, so are the same harmed or dead hearts. Nalan Xinde has begun the poem from a very classic Far Eastern image — the fleeting crows in the evening — the main character standing in a calm and quiet chamber, the snow is falling and the blizzard is blowing, as the leaves of willows flying in the sky, suddenly a cold, freezing whisper of wind penetrates into the room, the flowers of plum in the vase become dry, withered, and the incense of heart has been burnt into the ashes, only some vague smell lingering around in the air. They are like some brief encounters of love in our life, glittering yet infertile. They may force our hearts to beat fiercely at that time, though splendid and abundant like blooming flowers, all then just result in naught, bleaching into a vast, lonely scene of deserted snowy wasteland in the end. Only some insensible fragrance of perfumes remaining in the deep, dark and spleen strata of our memory, sometimes their faded and vague visages of the bygone golden days may still be casted onto the mottle and obscure night-screen of our life…

Perhaps the reason why the two great poets utilized totally contrary methods to write the nearly identical images can be traced back to the different cultural traditions and ideologies in æstheticism: Prudhomme wrote from the flower verbena, depicting the entire canvas step by step under his brushes, trying to describe the details of the images as clearly as possible. No matter the verbena, the sound of the blowing, the crystal material of the vase, the slowly spreading cracks, the leaking and dripping water and the flowers withering in the end, all of them were unfolded in the order, step after step as time goes by. And the image of vase and the image of heart were combined together predictably and naturally. Nalan Xinde, in the contrary, wrote the poem from a pretty common image in classical Chinese literature, using some rough strokes to draw and embellish a series of different images without any visible, predefined boundaries, only some blurry and sticking transitions as the montages in film. The series of juxtaposed images themselves have generated some poetic scenes and imaginations, which are far more beyond the scope and description of a single clip or footage. No matter the crows in the evenings, the obscure chamber, the snowflakes, the whisper of the wind, the vase or the heart-shaped incense, the poetic linking of all these traditional Eastern classic æsthetic images is a rather interesting and emotional scene in itself. In another word, Prudhomme has utilized the method in traditional Western realistic oil painting: starting from study of sketches and drafts, constructing the canvas and main object step by step rationally. Before holding his brushes to paint onto the canvas, the artist has carefully thought about the composition, shapes and colours, which would bring a foreseeable result in the end. Nalan Xinde, in the opposite, utilized a more causal, elegant yet freehand method somewhat similar to the traditional Far East paintings without predefined, fixed or rigorous pondering in style. The Cipai(詞牌, name of the lyrics/tones) only supplies a kind of possible example and structure for references, just like a manual in traditional Chinese paintings. The artist has only set and painted a little, vague colours among the black and white lines of silhouettes, causally ornamenting different scenes to link varies of images together, creating some splendid and gorgeous shots with narrative effects by interweaving and transiting different scenes and canvas together, leaving a lot of blank and hollow spaces for imagination. Just as the white space on the canvas in traditional Chinese paintings and the mute in the music, the audience and the readers will certainly fill them with their own abundant and deep meanings from their personal experiences and imaginations.— Fairly, we can simply say that both are completely contrary methods and styles in the art, one is rational, precise and devoted, focusing on the completion and independence of a single image; the other, on the other hand, is sensible, causal and natural, yet lingering among the poetics and beauty arousing from the different relationships between canvas and images.

It can be said, that these two poems are the best and wonderful example of “Apollinisch (Apollonian, [5])” and “Dionysisch (Dionysian, [5])” in poetry: one is crystal-clear, cold and outward-seeing, like the vision of Apollo’s(Απόλλων) insight observing all the details with precise and distinctive logic, trying to avoid any possible blurs in any details; the other is fussy, vague and blurry, sensible yet self-meditating, like the forever half-awake, half-asleep, drunken Dionysus(Διόνυσος). The boundaries between the inner world and outer world are not clean or clear, series of events are happening randomly without any concrete, specific relationships or direct logics, there are plenty rooms for possible multi-purpose explanations in details; In some significances, these are from the differences between Western cultural spirits and Eastern cultural spirits: the members of East Asian Languages, like Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese(CJKV), are not good at defining precise, detail-oriented descriptions, contrary to the West European languages generated from ancient Greek and Latin, languages like Chinese have no differentiations in grammatical genders of nouns(male, female or neutral), no differentiations in grammatical numbers, no precise definition of time(tense) or places, even no specific forms in different voices or direct/indirect speeches. The meaning of these words and sentences are largely based on the linguistic context of the text with multiple possibilities of significations and explanations— some are even contrary to each other. And maybe that’s one of the reason why the nearly identical images in these two poems of different languages(Chinese-French) can produce such different and varied effects finally. Because the basic foundation and material of poetry is the language, the differences in languages themselves can bring the two entirely contrary effects in Art.

Perhaps when we human were building the Tower of Bable(ܡܓܕܠܐ ܕܒܒܠ, מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל, [6]), God was not only preventing us from the paradise, the realm of gods is not only forbidding the feet of men, but also God was implying to us that the differences and variations in languages will generate different beauties and sentiments, from this moment on, our lives and world have being becoming so abundant and colourful…

Notes:

[1]. Sully Prudhomme (1839-1907), a famous French poet, the first winner of Nobel Prize in Literature.

[2]. Nederland (Nederduits), a historical geographic term, including Nederland and parts of Belgium, a lot of famous artists and painters came from this region since 17th century.

[3]. Nalan Xinde (納蘭性德, 1655-1685), a famous Chinese poet in Qing Dynasty.

[4]. Montage, is a film editing technique in which a series of short shots are sequenced to condense space, time, and information.

[5]. Apollinisch-dionysisch (Apollonian and Dionysian), The Apollonian and Dionysian is a philosophical and literary concept and dichotomy/dialectic, based on Apollo and Dionysus in Greek mythology. Some Western philosophical and literary figures have invoked this dichotomy in critical and creative works, most notably Friedrich Nietzsche and later followers.

[6]. Tower of Bable (ܡܓܕܠܐ ܕܒܒܠ, מִגְדַּל בָּבֶל), narrative in Genesis 11:1–9 is an origin myth meant to explain why the world’s peoples speak different languages.

蘇利·普呂多姆

聲明: 本篇音樂來自克勞德·德彪西(Claude Debussy)的《G小調小提琴奏鳴曲(Violin Sonata in G Minor)》第一樂章(I. Allegro vivo),小提琴: 姜東熙(Dong-Suk Kang), 鋼琴: 帕斯卡爾·德瓦雍(Pascal Devoyon), 來自專輯《法國小提琴奏鳴曲集(French Violin Sonatas)》No. 8.550276, DDD, Naxos(1989), 題圖原圖為讓·西美翁·夏爾丹(Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin)的《靜物, 瓶中花(Nature morte, fleurs dans un vase, vers 1760-1763)》蘇利·普呂多姆及納蘭性德圖片來自國際網路,部分詞條解釋來自維基百科(Wikipedia), 其它文字、法文、英文翻譯及圖片均為原創,請勿用於商業用途,謝謝!