本文最初發表於我和妻子的微信公眾號: 人面魚Fisage, 有增改。

一、布爾喬維亞

布爾喬維亞(bourgeoisie, [1])最早是擁有一定權利和財富的自由民(freedman, [2])和市民(civic)的總體代稱,歐洲中世紀以降,他們代表了民眾裏擁有一定話語權和資源的絕大多數人群,是社會的中堅力量和主要成員。但在近現代,布爾喬維亞卻被視為是介於貴族、上流階層與下層民眾之間搖擺不定的階層,他們沒有堅定不移的理念和態度,缺乏犧牲精神與擔當勇氣,只在乎自己的既得利益和外在名譽,以至於“布爾喬維亞”已成為某種意義上的貶義詞。

二、總有一頓永遠吃不上的午餐

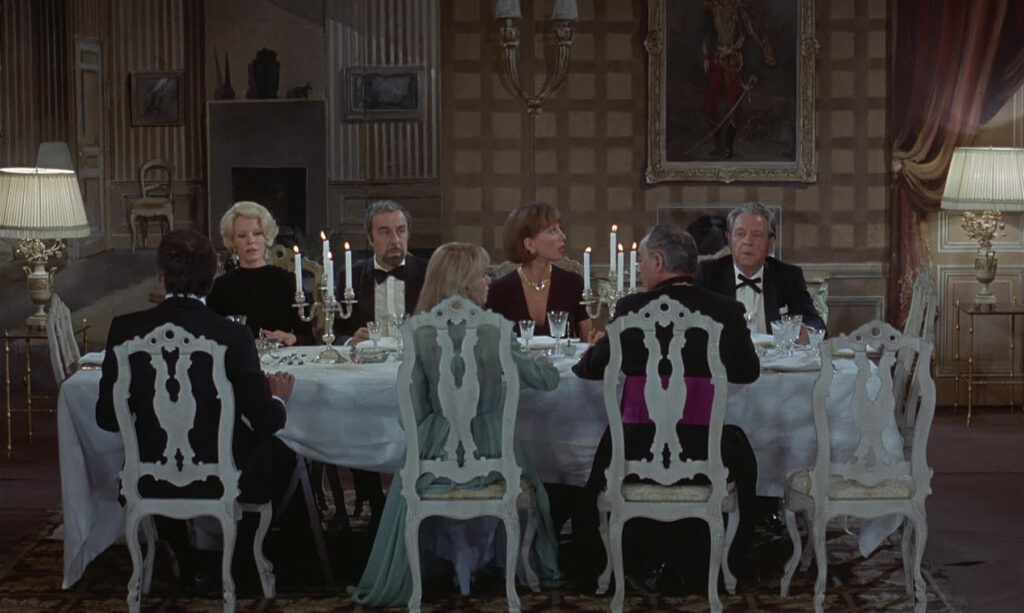

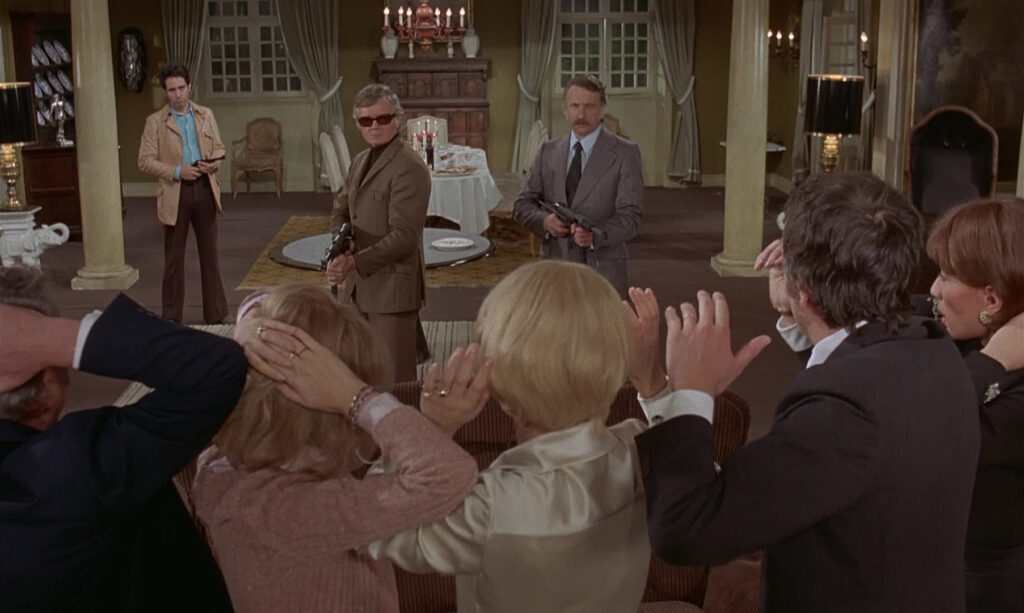

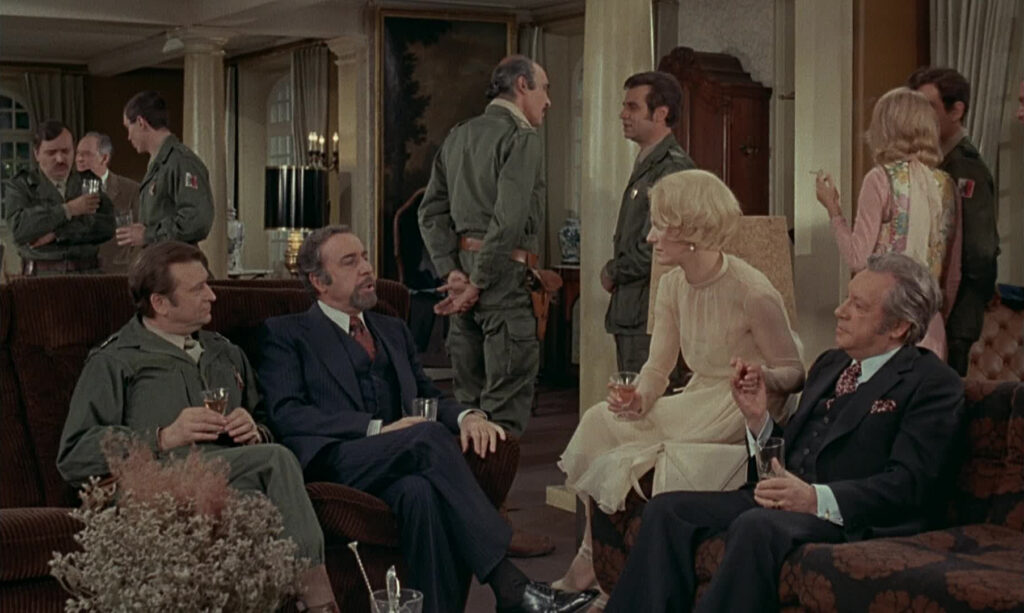

電影以一群希望聚餐的中產階級不斷被打擾之故事展開: 在一個以酒會、派對和宴會作為交際緣由的人群裏,衣冠楚楚的男人和金光閃閃的女人們藉著各種各樣漂亮美麗的面目外表,在彬彬有禮的交談和觥籌交錯間,通過利益交換達成了各自不同的目的: 不管是毒品交易、綁架劫殺、恐怖襲擊、還是通姦偷情,聚餐和宴會的目的本身並不重要,人們在意的只不過是一個可以達成交易之場所與可能的談判桌,或者探討實施其罪惡計劃的工作室,附帶著感官外在的刺激和別樣的滿足,以及在外人看來的優雅和高貴光環下掩藏的赤裸慾望與勃勃野心。在款款溫情的面紗和精緻美妙的面具下,不同的人通過或文雅或幽默或精彩的言語,激烈地商討著如何分配他們可能的利益。而不斷被各種意外事件強制中斷的聚餐,就不啻於是對這類生活最大的諷刺與極盡的挖苦。

三、生之歡愉及幻滅

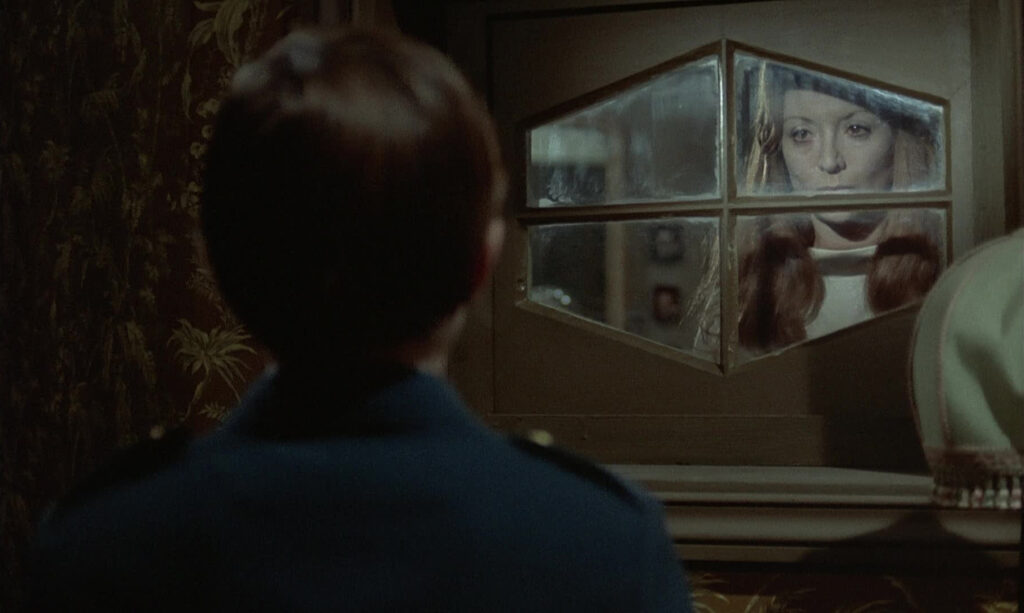

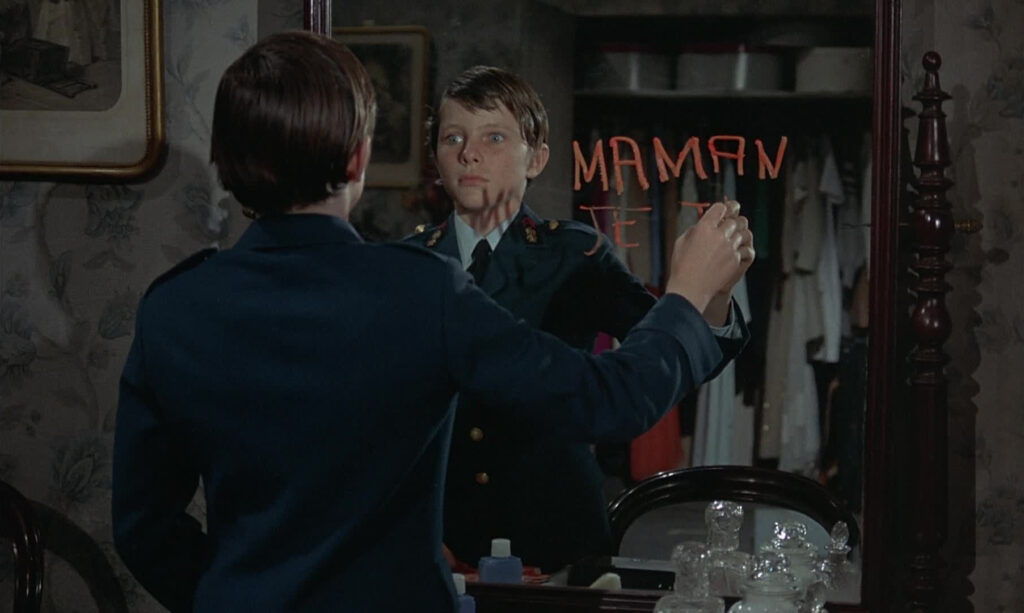

人生苦短(Ὁ βίος βραχύς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή, Ars longa, vita brevis, [3]), 對於人類這種朝生暮死,蜉蝣一夕的種族來說,一輩子也不過是短短的一週。在我們這個社會被文明過度馴化和階層嚴重固化的時代,幾乎每個人的生命其實都是一條可以被看到盡頭的繩索,差別的只有長短、尺寸和重量。每天重複的時日,不過是一次又一次地證明生活的無聊與一成不變–當然,我們也可以認為,“無聊”本身,也是一種對抗“生之虛無(Néant de la vie, [4])”的一種手段–不管是誰,每個人都只願意躲在個人感官製造的舒適區裏一動不動,在暖洋洋的白日夢蒸發的麻痺幻覺裏醉生夢死,日復一日地觀看著命運早已安排好的同樣戲劇,而生命,自己的生命,卻在這自我重複和自我僵化中,漸漸地逐步淡化,最終消逝湮滅於命運之深處······中產階級天生的優越地位和有利條件,使得他們可以早早地安排自己和子女的未來生活,盡可能地避開各種不可預料的風險與災難,在“不確定”的叢林裏行走在父輩為他們開拓的道路上: 殊不知,在規避危險與不確定的同時,他們也同時放棄了人生道路上未被發現與發掘的壯美,未知和不確定,本身即是風險,更可能是機遇,永遠遵循先人的道路,只會讓我們的大腦被刻上同樣的迴路與軌道,並最終使之慢慢萎縮,成為習慣的奴隸和成規的僕從–生活的消失不在於肉體的終結,而在於精神上的枯萎和不育。沒有風險和未知的生活,就像是失去水分卻色彩豔麗的標本,在玻璃罩裏,完整、美麗、精緻、可以被控制,可以被觀測,也可以被預計,但是沒有水分,沒有生命,更沒有活力。

四、論無瑕名譽之可能性

外人很難理解中產階級對於外在看法和他人眼光的重視與在意,但其實,只要身處其中,我們就很容易明白個中緣由: 因為,“名譽”, 或者“聲望”對於一個時刻需要外部安全感支撐和上流社會首肯的階層來說,“正經”而“端莊”的名聲不亞於是一張通往更高階層的通行證: 一個風評糟糕的中產階級是無論如何沒法進一步打入上流社會的交際圈。同時,因其自身掌握的資源和優勢地位,在面對人性中固有的陰暗面和骯髒慾望,在他們光鮮亮麗的外表和冠冕堂皇的言語反襯下,就更顯得齷齪刺目。所以,“偽善”和“虛偽”就成為他們最常批於周身的最佳外套,而“正派”和“賢淑”也就成為了每個中產階級必備的素養及品德,我們通常很驚訝於他們之中驚人數目的“偽君子”和“假淑女”, 卻往往不明其就–只有一個善於偽裝和八面玲瓏的人,才有資格與上流社會的菁英和名流們出入往來,相與甚歡。同時,他們還要小心,不要被來自下面階層的人們所取代或推下,時刻涇渭分明地保持著與他們的距離和差別。

五、布努埃爾

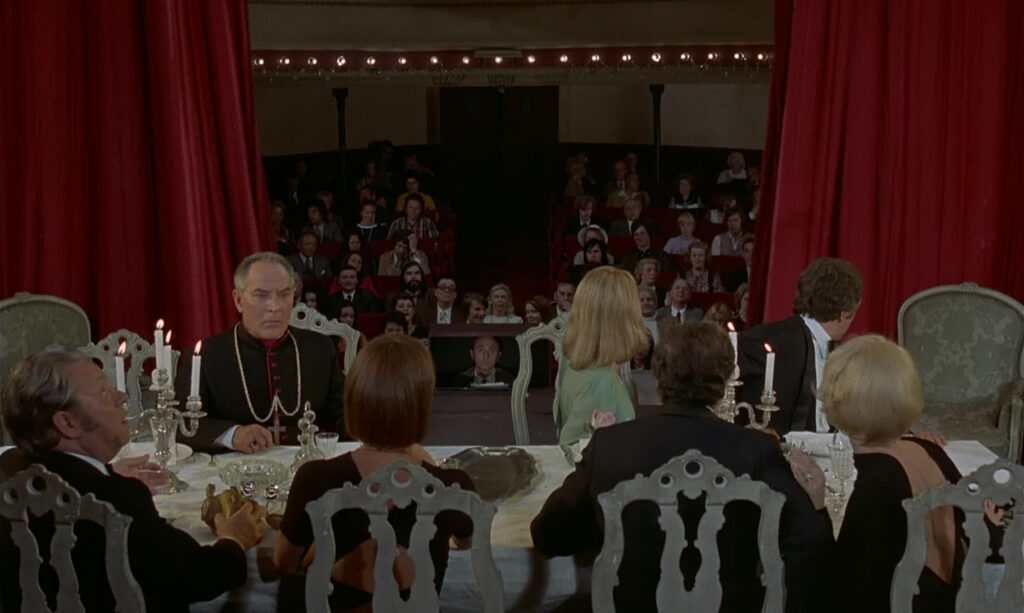

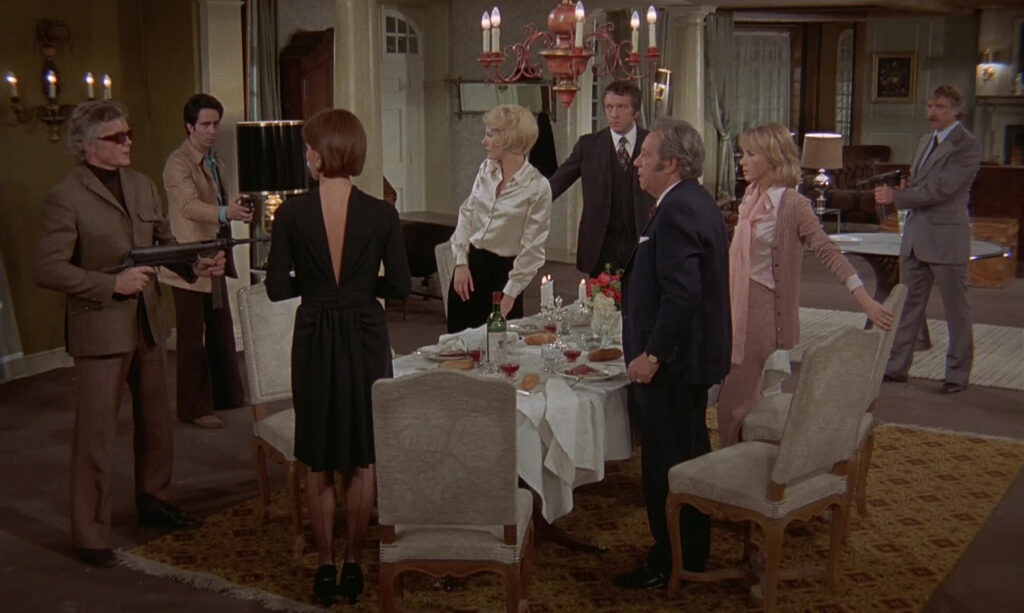

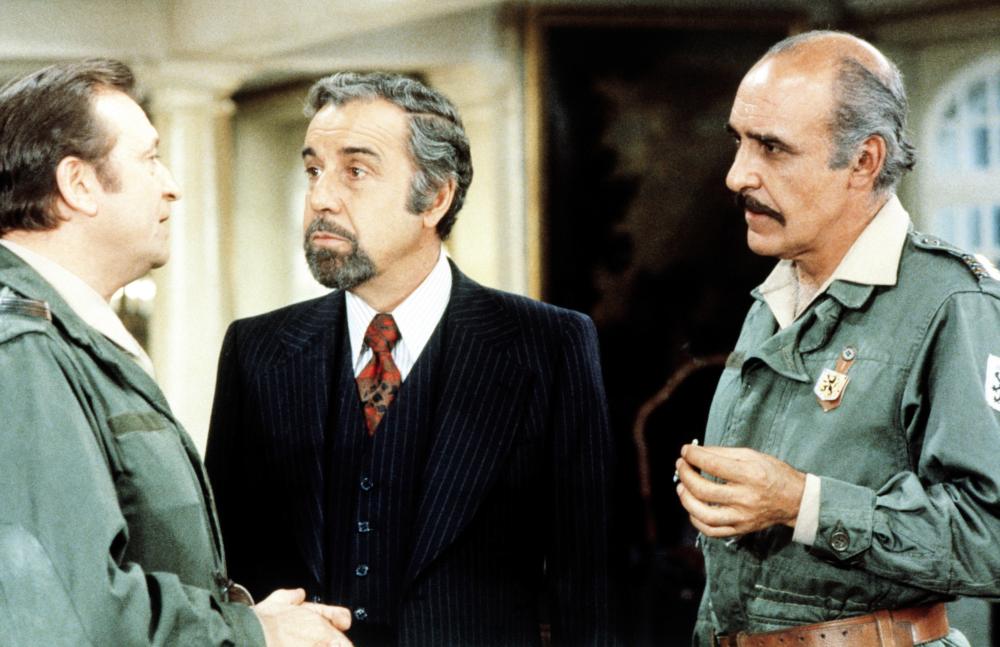

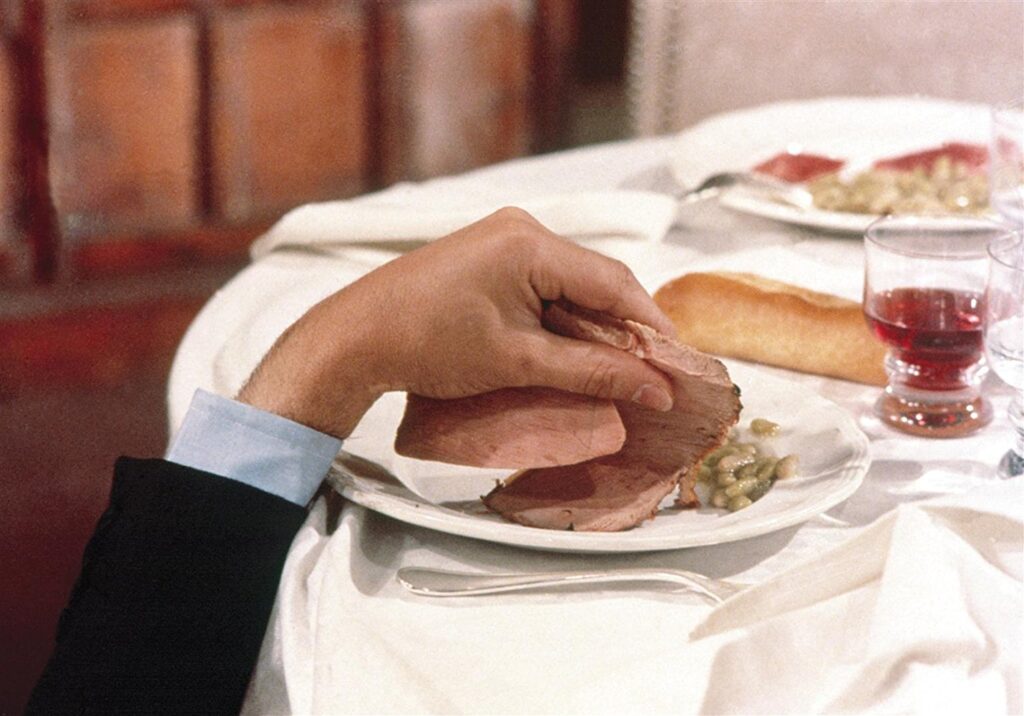

路易斯•布努埃爾(Luis Buñuel, [5])出生於一個篤信天主教的中產階級家庭,他從小就對這種的生活瞭然於胸,身邊人們的言行舉止,無一不是透出一種穿著鎧甲,謹小慎微而無聊的味道。他們小心翼翼地維持著自己的生活方式,每日重複,深怕別人嘲笑和議論。他巧妙地安排著一連串看似巧合的夢境,不管如何荒謬,如何驚奇,總能使得劇情得以敘述,混合超現實主義(Surréalisme, [6])夢境般的神奇和不可思議,同時又要保持著適度而令人信服的真實感,比起驚世駭俗的《一條安達魯的狗(Un Chien Andalou), [7]》, 也許更為困難,包含的意象和象徵也更為豐富多彩: 和豐盛晚宴同時同地進行的葬禮與悼念儀式; 造訪他人卻無意間成為舞臺戲劇裏的演員; 聚餐時被突如其來的恐怖主義分子入室掃射屠殺,男主角還不忘偷吃餐桌上的烤羊腿; 母親的亡魂通過自己的孩子完成了情夫念念不忘的復仇; 在聽取臨死禱告時對殺害父母仇人即刻進行血親復仇的主教–最後,他還不忘再次嘲笑揶揄天主教慈悲和寬恕的虛假–或者,當宗教信仰已經淪為支撐階層自尊和虛榮的藉口和統治壓制之理由時,它不過就是一件“皇帝的新衣(Kejserens nye Klæder, The Emperor’s New Clothes, [8])”。每一次看似不可思議的死局和幕落,都被一個個人物從夢中驚醒所重新開啟續章。每一個隨機的巧合都同時指向一件永遠無法完成的事情–聚餐。間或穿插人們“在路上(en route)”的場景,就類似於《銀河(La Voie Lactée), [9]》裏尋求真理的不同信仰者: 追求真理或朝聖的目的本身並不重要,重要的不過是追求的過程。

六、精神分析

如果我們更進一步地觀察,從精神分析學上解釋,與喪葬“死”的意象相對,我們可以把“聚餐-進食”視為“生”之慾望的影射:“聚餐-進食”帶來的是生命的延續與延長,而不斷被打攪的“聚餐-進食”意象就是被其之外的力量不斷打破之象徵。上尉敘述的不幸童年,正是弗洛伊德(Sigmund Freud, [10])反覆闡述的孩童時代經歷對於人一生塑造之決定性作用。而夢境,往往是在現實生活中得不到宣洩滿足的慾望和情感之折射,一個套著另一個的夢境,以各種各樣激烈而突兀場景戛然而止–或暴力,或血腥,或可怖,或憂傷–有時候,我們並不能區分夢境與真實的差別: 誰說,人生又不是一個更為清醒的夢境?

須知清醒乃是另一種沈眠 而無夢之夢以及死亡 那我們的血肉所畏懼之死亡 每個夜晚,它均自稱睡眠。 J. L. 博爾赫斯 《詩藝》 Sentir que la vigilia es otro sueño Que sueña no soñar y que la muerte Que teme nuestra carne es esa muerte De cada noche, que se llama sueño. J. L. Borges, “Arte Poética”, [11]

七、一個關於身分的劇場

導演巧妙地安排了來自同一階層的不同之角色通過劇情產生關聯: 其中有政治家,有商人,有知識分子,有軍人,有家庭主婦,還有宗教人士,他們共同組成了一個可以彰顯當時社會氛圍的縮略圖。在這個精緻微小的舞臺上,肩負起典型角色的形象和性格,演員們遵循著西方古老的戲劇傳統,在高度濃縮的故事裏,於矛盾的衝突和激化中,演繹出小社會的荒誕、奇怪與不可思議。

老彼得·勃魯蓋爾: 死亡之勝利

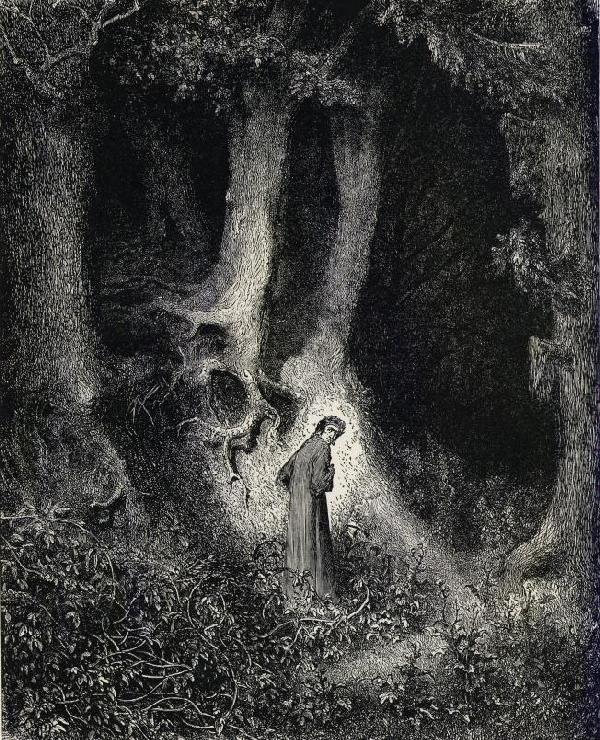

古斯塔夫·多雷: “在我們生命之途的半程···, 《神曲·地獄篇》”

漢斯·梅林: 最後的審判

八、生死之魅

死亡一直是令布努埃爾著迷不已的主題動機,亡魂的執念和逝去的親人,都是我們過往生活的眷戀與不捨。我們知道人鬼殊途,我們也知道失去的就永遠不會再出現,但我們的情感永遠都不會放棄這份依戀和懷念。誤入夢境和亡靈來相會,都是我們的本能之一–“向死之存在(das Sein zum Tode, Being toward death, [12])”: 沒有死亡,就沒有新生,沒有人生短暫的感嘆,我們就越發不會珍惜當下的幸福。死亡崇拜一直根植於歐洲文明的古老傳統之中,不論是額我略聖歌(Cantus Gregorianus, [13])《神怒之日(Dies iræ), [14]》, 還是《死之舞(La Danse macabre), [15]》, 還是《神曲(Divina Commedia), [16]》裏暢遊地獄、煉獄和天堂的詩人但丁(Dante, [16]),抑或是萬聖節裏出遊的骷髏,在對死亡和往生世界的思考和嚮往裏,我們的生命才會更加精彩。亡靈和逝者與我們處於同一時空,才能時時提醒我們留意生命的脆弱、不安和寶貴,而永遠無法彌補的缺憾與不完美,曾經可能的交集和不可再續的前緣,則帶來“物哀(物の哀れ/もののあはれ, [17])”之感嘆和“缺憾美”–死亡,不應該是我們需要刻意規避的痛苦與不完美,應該是我們本身生命的一部分,在與每個逝者的心靈傾吐和神交懷戀中,我們更意識到生命的侷限、珍貴與不可替代。在“回憶”這看不見的珍藏裏,我們可以盡情盛放曾經的感動、期盼和希翼,還同時可以感知並聆聽到命運的真諦和意義。

2017 Oct. 05~07, 2021 March 25, Aug. 15

米開朗琪羅: 最後的審判

註釋

[1]. 布爾喬維亞(Bourgeoisie), 原意指在村落城市中居住的自由人,在近現代,主要指具有一定財產,擁有人身自由,介於上流菁英貴族與底層之間的社會階層。

[2]. 自由民(freedmen), 指擁有基本人身自由、不被奴役的人,享有基本的政治和經濟權利,是奴隸的相對群體。

[3]. 人生短暫,藝術永恆(Ὁ βίος βραχύς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή, Ars longa, vita brevis), 古希臘哲學家希波克拉底(Ἱπποκράτης, Hippocrates)的箴言。

[4]. 生之虛無(Néant de la vie), 來自德國哲學家叔本華(Arthur Schopenhauer)的哲學概念,進一步被海德格爾(Martin Heidegger)以及往後的薩特(Jean-Paul Sartre)等存在主義哲學家深入闡釋,意指人類因自我生存本身產生的本源性、存在性焦慮。

[5]. 路易斯•布努埃爾(Luis Buñuel), 西班牙二十世紀最偉大的電影導演,與薩爾瓦多·達利(Salvador Dalí)等著名藝術家創立並參與了超現實主義運動,代表作品為《一條安達魯的狗(Un Chien Andalou)》,《黃金時代(L’Âge d’or)》等。

[6]. 超現實主義(Surréalisme), 二十世紀最重要的文化藝術運動,基於弗洛伊德的精神分析理論,強調潛意識、無意識、夢境以及性衝動在文藝創作中的巨大推動力。

[7]. 一條安達魯的狗(Un Chien Andalou), 布努埃爾的成名電影,當時甫一公映,就帶來了巨大的社會風波和衝擊。

[8]. 皇帝的新衣(Kejserens nye Klæder, The Emperor’s New Clothes), 安徒生(Hans Christian Andersen)童話中的著名故事,意指因為不敢揭穿的謊言產生的大笑話。

[9]. 銀河(La Voie Lactée), 布努埃爾的一部電影,講述幾個人在朝聖尋求信仰的路上遭遇的形形色色的人和事。

[10]. 弗洛伊德(Sigmund Freud), 現代精神分析(Psychoanalyse)理論的創立者和奠基人,被視為二十世紀最偉大的心理學家,其學說對於多個領域都具有強烈、持久而巨大的影響。

[11]. J. L. 博爾赫斯(Jorge Luis Borges), 阿根廷人,被視為二十世紀最重要的西班牙語詩人和作家。

[12]. 向死之存在(das Sein zum Tode, Being toward death), 德國哲學家海德格爾主要的哲學概念之一,意指人類因爲死亡這個不可更改的事實而產生的相其之傾向和趨勢。

[13]. 額我略聖歌(Cantus Gregorianus), 被認為是教宗額我略一世發明的基督教單聲聖歌,是一種單聲部、無伴奏的天主教會宗教音樂。

[14]. 神怒之日(Dies iræ), 一首天主教的繼敘經,收錄於《常用歌集》內。

[15]. 死之舞(La Danse macabre), 中世紀藝術的體裁之一,主要形象是正在舞蹈的骷髏,象徵生命無常和脆弱。

[16]. 神曲(Divina Commedia), 義大利詩人但丁(Dante Alighieri)的代表長篇詩歌,講述詩人在地獄、煉獄和天堂間遊歷的見聞。

[17]. 物哀(物の哀れ/もののあはれ), 日本平安時代重要的審美理念之一。主要是通過描繪一些蕭瑟、殘敗、荒涼的景物,來表達哀傷幽情,以及對人世無常之感慨。

EN

Le Charm Discret de la Bourgeoisie

I. Bourgeoisie

In the beginning, the word “bourgeoisie, [1]” was a common term referring to the freedmen [2] and civilians with certain rights and wealth in the town. Since the Middle Age in Europe, it has been standing for the majority of the people with certain political rights and social resources among many. But in the modern times, the bourgeoisies are regarded as a class swinging between the aristocrats and the lower social strata. Without ambitious ideology and strong attitude, without spirit of self-sacrifice and courage of undertaking, they only care for their own vested interests and fames in the eyes of others’, as a result, the word “bourgeoisie” has somewhat become a derogatory term in the meaning.

II. There’s Always a Lunch You can Never Eat

The film was unfolded via a set of bourgeoisie’s unsuccessful wish to have a dinner together with endless interruptions. In a group of people with the excuses of cocktail, parties and banquets for the social intercourses, hidden beneath the various, beautiful, pretty and charming visages and appearances, with the polite conversations and cheerful drinks, men with righteous suits and women with splendid, blinking jewelries have earned their different goals along with exchanged benefits: no matter the drug dealing, no matter the kidnapping or killing, no matter the terroristic attacks, or even the adulteries and infidelities, the aim of dinner or banquet has no importances. The main concern for them is just a suitable place or a probable negotiating table for a deal, or a possible studio to discuss and carry out their evil projects, with exteriors stimulations and extraordinary satisfactions for sensations, while concealing to others the most naked desires and the widest schemes behind the so-called elegant and glorious halos. Under the delicate masks and soft, gentle veils, people are talking and discussing how to share their possible interests by those polished, humorous, brilliant, smart or wonderful words and phrases. The dinner forcibly interrupted by different accidents or events is the biggest irony and grandest torment for this kind of life.

III. The Happiness and Ephemera of Life

Ars longa, vita brevis (Ὁ βίος βραχύς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή. Art is long, life is short, [3]). For a race with such short life that birth in the morning while death in the evening like human, the entire life is merely a week. In the epoch when our society has been over-tamed by the civilizations with strictly rigged social strata, nearly everybody is just a thread stretching to a foreseeable end, with the only differences in length, size or weight. The repeated days just mean to demonstrate the boring of the life and its indifferences again and again– perhaps we can regard the “boring” itself as a way to fight against the “Néant de la vie (Nothingness of the life, [4])”— All try to hide themselves and stay safely in the comfortable zones produced by their senses, dreaming in a lukewarm, numb illusions evaporated by the phantoms from their daydreams, watching the same plays and theatres planned and set by the destiny again and again, day after day, though the life, their own life, are fading and fleeting, in this self-repetitions and self-paralyzations, vanishing and diminishing into the obscure depth of the fates… The bourgeoisie’s intrinsic, innate privilege in the social status and conditions make them fore-plan the future life for themselves and their offsprings, avoiding most unpredictable and unexpected disasters and dangers as much as possible, forwarding “en route” explored and widened by their forefathers in the jungle of “uncertainty”: with no knowledges that at the same time of avoiding the dangers and uncertainties, they’ve also given up the wonders and beauties never discovered by someone else on their ways of life. The unknowns and the uncertains, indeed, are risks and ventures, but they may also be some good chances and opportunities. Following the old, original road set by our ancestors and predecessors forever will definitely carve in our brains the same tracks and sulci, making the brains atrophy and shrivel little by little, turning ourselves into the slaves of the habits and the servants of the rules— the dissipating of the life is not the termination of the body, but the withering and infertility of the souls and spirits. Life without risks and uncertainties, is like torrid yet colourful, vivid specimens covered in the glass, complete, pretty, delicate, controllable, detectable, predictable, but dry without water, static without life, rigid without vitality.

IV. On the Possibility of Perfect Reputation

The outsiders may have difficulties to understand bourgeoisie’s paranoid attentions and extreme carefulness about others’ critics and opinions. In fact, if you are one of them, it is so easy to comprehend that: as the “Fame” or “Reputation” means so much to the social class requiring approvals from the upper classes and senses of security from the outside world to support themselves. A “decent” or “dignified” reputation will indisputably be a passport to help them enter the upper classes: a bourgeoisie with disgraceful or infamous reputation will never be invited to step into the circle of the upper classes. Yet at the same time, especially, with their privileged social status and resources, their inner, inherent, hidden, dark side of the humanity and dirty, gloomy desires will be spilled and stained much more nastily and harshly on the brilliant background of their shining, vivid outfits and highfalutin, justified words and sentences. In such a way, frequently, the “hypocrisy” and “pretence” will be the perfect coat that suits them the best. And that’s why “decentness” and “virtuousness” have become the most necessary and saught-after quality and characteristic for every proper bourgeoisie. It is no wonder that we may surprise by the overwhelming number of the “hypocrites” and “fake-ladies” among this class with no visible clues— only those with excellent abilities to hide their true wills while maintaining a quite good relationship with the majorities will earn their chances to have contact or even “friendship” with the élites and celebrities from the upper classes. And, in the meanwhile, they still should be careful and cautious to never let themselves be over-thrown and replaced by members from the lower classes, always distancing themselves from them and differentiating themselves from them.

V. Luis Buñuel

Luis Buñuel [5] was born in a bourgeoisie family with faithful belief in Catholicism. Since his childhood, he had been familiar with this kind of life. People around him, their actions and words, all appeared with some type of discreet, cautious and boring atmosphere as if they were wearing the amours all day long. They were so vigilant to take care of their life styles, repeated it day after day, fearing the mocking and gossiping from others’. He has arranged series of coincidental and accidental dreams skillfully so that the plot can go on, no matter how ridiculous, no matter how bizarre it may seem. Compared to the once thrilling and shocking masterpiece “Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog, [6])”, mixing the marvels and unbelievable dreams of Surréalisme [7] while still keep some comfortable degrees in trust-worthy sense of reality might be much more difficult with so many lavish, complicated and colourful images and symbols: an abundant dinner with a funeral and mourning ceremony at the same time in the the same place; main roles visiting somebody’s but suddenly becoming the players in the theatre on the stage; some terrorists breaking into the chamber and killing all guests, yet still, a main male character trying to steal the grilled lamb legs on the table to eat; a ghost of a mother taking her obsessed vengeance against her husband for her lover by the hands of their son; and a bishop revenging the murderer of his parents while listening to the final confession of a dying old man— in the end, Buñuel never forgets to scoff and sneer the vanity and sanctimony of Christian’s mercy and forgiveness— the religion is simply just “Kejserens nye Klæder (The Emperor’s New Clothes, [8])” when it has degraded and degenerated into excuses for supporting the vain-glory and self-esteems of the social classes and causes for suppressing reigning and ruling. Every incredible and unbelievable dead-ends or cut-of-scenes would be resumed and continued by the sudden awakening from nightmares of the main characters, unrolling and revealing the succeeding new chapters. And all the random coincidences and serendipities were pointed to a never-successful event— eating dinner together. The scenes of people “en route” inserted and interwoven among different shots are similar to the various believers pursuing truth and faith in the film “La Voie Lactée (The Milky Way, [9])”: the pilgrimage or the truths themselves are not significant, but certainly is the process of pursuing it.

VI. Psychoanalysis

If we analyze further more and explain the film by psychoanalysis, contrary to the image of “Death” in the funeral, we can regard the “Dinner-eating” as a reflection of the desire of “Life”: the “Dinner-eating” gives us the meaning of prolonging and expanding of the life, while the image of “Dinner-eating” interrupted endless can be considered as a symbol of life broken by other forces. According to Sigmund Freud [10], the melancholy childhood told by the lieutenant is a good explanation of the concept that the life and experience of a child will be a major, deciding contributor/factor to shape his/her entire life. And the dreams are the reflections of those unsatisfied and unfulfilled desires and emotions in one’s real life. A dream inside another, frozen or muted by diverse, violent and unexpected scenes— be that brutal, be that bloody, be that frightening, or be that sorrowful— sometimes, we can even be unable to distinguish the dreams from the reality: how dare we say that the life itself is NOT another sober dream?

Sentir que la vigilia es otro sueño Que sueña no soñar y que la muerte Que teme nuestra carne es esa muerte De cada noche, que se llama sueño. J. L. Borges [11], “Arte Poética”

VII. A Theatre about Social Status

The director has arranged all kinds of typical roles and characters to link with each other through the whole story: there are politicians, merchants, intellectuals, soldiers, housewives and religious figures. They together have formed a small thumbnail to represent the current social conditions and atmosphere of the entire society. On this delicate and tiny stage, with the images and characteristics of various classical roles, the performers have followed the ancient tradition of the Western theatre to interpret the weirdness, estrangement and incredibility of the small society in the highly condensed plot through the conflicting and intensifying contradictories.

VIII. The Charm of Life and Death

Buñuel is always fascinated by the motif “Death”. The obsession of the ghost and the dead relatives are all our love and miss for our bygone period. We surely know that the deads and the livings can never be together, and we certainly see that the losts will never reappear again, yet our emotions will never relinquish this attachment and nostalgia. Lost in dreams or meeting ghosts is one of our basic instincts— “das Sein zum Tode (Being toward death, [12])”: without death, there will be no birth; without the signing of the short life of human, we will never cherish our life at the present moment. The worship of Death has been deeply rooted in the ancient tradition of European civilization, no matter the Cantus Gregorianus (Gregorian plainchant, [13]) “Dies Iræ (Day of Wrath, [14])”, no matter the “La Danse macabre (Dance of Death, [15])”, no matter the poet Dante’s involuntarily travelling from Inferno (Hell) through Purgatorio (Purgatory) onto Paradiso (Paradise) in his masterpiece “Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy, [16])”, or even the skeleton in the parade on Halloween, it is only in the pondering and yearning of the death and the other side of the world, our lives appear much more wonderful and meaningful. The ghosts and the deads existing at the same time and in the same space with us just mean to remind us the fragility, unnerving and preciousness of our lives from time to time. The never-completed losts and imperfects, the once possible intercourses and bygone relationships just send us the exclamations of “mono no aware (the pathos of things, 物の哀れ, [17])” and the “beauty of imperfection”— The death should never be the pain or imperfection that we have to avoid deliberately, but a necessary and undispatchable part of our own lives. In the spiritual confiding or the affecting fondness between the souls, we finally realize even more the limits, the invaluableness and irreplaceableness of our own lives. In this invisible, priceless collections of the “Mémoire”, we can save all our touchings and movings, expectations and hopes freely yet still feel and listen to the true meanings and essences of the destiny.

2017, Oct 05~07, 2021, March 25, Aug. 15

Notes

[1]. Bourgeoisie, this word comes from French, it means that “those who lives in the town and city”, now it stands for the middle class in the society.

[2]. Freedman, is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery.

[3]. Ars longa, vita brevis (Ὁ βίος βραχύς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή. Art is long, life is short), a famous citation from Hippocrate’s saying.

[4]. Néant de la vie (Nothingness of the life), a fundamental concept from Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, means the voidness and anxiety in ones conscience of self-existence.

[5]. Luis Buñuel, the most important Spanish director of the 20th century, his main surrealist films are “Un Chien Andalou“, “L’Âge d’Or” etc.

[6]. Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), Buñuel’s famous surrealist film, causing a lot of social controversies at the time of its releasing.

[7]. Surréalisme, a cultural movement which developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I and was largely influenced by Dada.

[8]. Kejserens nye Klæder (The Emperor’s New Clothes), a literary folktale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, about a vain emperor who gets exposed before his subjects.

[9]. La Voie Lactée (The Milky Way), a 1969 surrealist film directed by Luis Buñuel, the plot is about the pilgrimage of “searching for truth”.

[10]. Sigmund Freud, an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, the most influential neurological theory in the 20th century.

[11]. Jorge Luis Borges, an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, and a key figure in Spanish-language and universal literature.

[12]. das Sein zum Tode (Being toward death), another famous and fundamental concept in Martin Heidegger’s philosophy, means the inevitable end/doom fate of the common people will bring one’s mind to another meaning of his/her own life.

[13]. Cantus Gregorianus (Gregorian plainchant), is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic, unaccompanied sacred song in Latin (and occasionally Greek) of the Roman Catholic Church.

[14]. Dies Iræ (Day of Wrath), a Latin sequence attributed to either Thomas of Celano of the Franciscansor to Latino Malabranca Orsini, lector at the Dominican studium at Santa Sabina, the forerunner of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas Angelicum in Rome.

[15]. La Danse macabre (Dance of Death), an artistic genre of allegory of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death: no matter one’s station in life, the Danse Macabre unites all.

[16]. Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy), a long Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri.

[17]. mono no aware (the pathos of things, 物の哀れ), literally “the pathos of things”, and also translated as “an empathy toward things”, or “a sensitivity to ephemera”, is a Japanese term for the awareness of impermanence (無常, mujō).

聲明: 本篇音樂來自匈牙利作曲家弗蘭茨·李斯特(Franz Liszt)的《死之舞,基於“神怒之日”主題,為鋼琴及管弦樂團而作(Totentanz, Danse macabre, Paraphrase über “Dies Iræ” für Klavier und Orchester)》, 鋼琴: 克里斯蒂安·齊瑪曼(Krystian Zimerman), 波士頓交響樂團(Boston Symphony Orchestra), 指揮: 小澤征爾(Seiji Ozawa), 00289 477 9697 GM2, Deutsche Grammophon(1988, 1991), 所有電影截禎及繪畫圖片來自國際網路, 其它文字、英文及西班牙文翻譯、圖片均為原創,歡迎轉發,請勿用於商業用途,謝謝!